I have often heard that the need to reduce population growth in African countries is less important than in rich countries because consumption is so much lower in Africa. It is true that the impact of a person in Africa is much less than someone in a rich country, however there are important but different reasons for Africans to reduce their fertility.

Although the average footprint of a person in Africa is small, there are already more feet than the land can bear in some places. Slowing population growth there will help people be healthier, happier and more productive. Traditions exist that are harmful to women and also lead to high fertility. These injurious traditions may have had their function in the past, but they have no place in the 21st century.

In the past I was a cultural relativist. I believed that the practices in other cultures shouldn’t be evaluated by our standards. When I learned about Female Genital Mutilation, I changed my mind. If one believes that girls and women deserve the same respect as boys and men, one cannot be a cultural relativist.

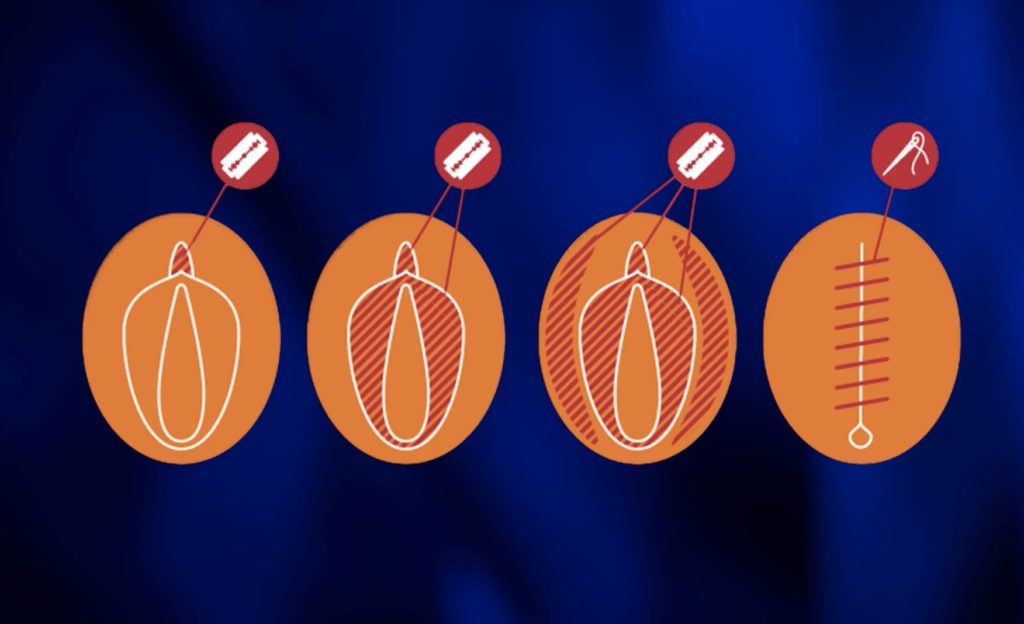

FMG is practiced by many cultures in Africa. It consists of removing part or most of the external genitalia of girls. It is usually done without anesthesia and often with a dirty blade.When the margins of the vulva are separated by the (brutal) slicing, acacia needles are used to hold them together. Think of the agony FMG survivors suffer! Some victims die from blood loss or infection. The pain returns during intercourse and childbirth if the vaginal opening has been sewn nearly shut. Fortunately, there are many organizations in Africa that are working to get rid of FMG. Often they substitute another, more benign, coming-of-age ritual for girls.

Child marriage is another damaging custom of some African cultures. Typically, the girl’s arranged marriage is shortly after she starts to menstruate, and she is forced to wed a man many years older than she. A girlchild is considered a burden in many societies, so the best way to get unburdened is to marry her off. Worse, rape of a young girl is not uncommon. Since virginity is a requirement for marriage in many societies, the girl’s parents force their daughter to marry her rapist. The pitiable girl is thus dominated by her husband for the rest of her life.

The psychological effects on a girl who is married as a young teen must be terrible, however the physical effects can be fatal. Her pelvis may be too small to give birth if she conceives before her bones have finished growing. Obstructed labor may kill the fetus—resulting in a stillbirth. Sometimes pressure of the fetal head against the girl’s pelvis blocks blood flow to the girl’s tissues. The dead flesh dissolves, forming a hole through which pee and/or poop can pour.

You might think that child marriage and FGM don’t exist in the USA, but that is wrong. Some immigrants practice both. In addition, some non-immigrant groups have allowed early marriage, often in response to early teen pregnancies. Delaware was our first state to ban marriage before age 18, only 4 years ago. Women who marry young tend to have more children and seldom advance far in education.

Both child marriage and FGM are means of subjugating women; so is cutting short their education. Another way power is taken away from women is the absence of something we take for granted—clean and safe toilet facilities at schools. Many girls quit school after their period starts because their school lacks adequate, private toilet facilities.

Where girls and women are treated as inferior, they have little control over their lives. They don’t have power over what happens to the most personal parts of their bodies, nor when or whom they marry. They may not say when they have sex, nor limit the number of children they bear, nor use contraception if they want to.

Many organizations work to empower African women by putting an end to child marriage and FGM. One favorite is the Population Media Center, which has made great advances in education about these evils.

Although I am not an anthropologist and have spent only a little time in Africa, these seem to be some reasons that the population is growing so rapidly there. In the future I’ll write about religions which encourage large families, and about overpopulation causing famine—one of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.

© Richard Grossman MD, 2022